In the early 1900s, Hot Corner was one of the most prosperous historically African American business districts in the South.

The intersection of Hull St. and Washington St., 1914 The Morton Theatre is in the top left corner. Union Hall (no longer there) is across the street. Hargrett Special Collections, MS1633a

Overview

Hot Corner, at the intersection of Hull St. and Washington St., supported a thriving African American business community and was home to the celebrated Morton Theatre, one the first black-owned and operated vaudeville theatres in the country. Walking through this part of downtown Athens, you may feel like you’re walking back in time. Each building here has a rich history that is still unfolding today.

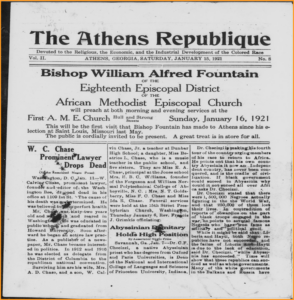

The Athens Republique, one of three African American owned newspapers in Athens, was located at 343 Hull Street.

The Athens Republique

In November 1919, recent World War I veteran Julian Lucasse Brown began publishing The Athens Republique. According to its masthead, the paper was “Devoted to the Religious, the Economic, and the Industrial Development of the Colored Race.” The Republique was also the official organ for the local Jeruel Baptist Association, which ran the Jeruel Academy, a private school for Black students in the city school for Black students in the city.

The paper circulated weekly on Saturdays and covered stories on the affairs of the African American community in Athens. The paper also regularly featured national reports of efforts to fight the Ku Klux Klan and lynchings across the country. Additionally, Brown devoted multiple pages of each issue to societal news in Athens and surrounding towns, including weddings, deaths, illnesses, and church events often ignored by the white-run press. In 1923, Brown relocated the paper to an office on Hull Street in the area known as the Hot Corner. Brown supplemented his journalistic endeavor by working as a notary, serving as secretary of the Allied National Farm Association (also headquartered on Hull Street), and selling printed materials out of his office. By 1927, the Athens Republique was no longer in business. In the decade that followed, Brown and his wife Katherine moved to Alabama, where he served as a teacher and printer at the Tuskegee Institute.

learn more at: https://gahistoricnewspapers.galileo.usg.edu/lccn/2012233098/

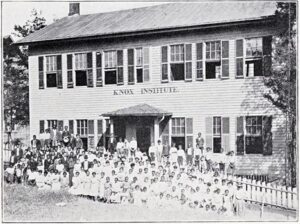

The Knox Institute, circa 1910. The Knox Institute, located at the corner of Reese and Pope Streets, was less than a mile of Hot Corner.

Reconstruction

Even during Reconstruction and Jim Crow, Hot Corner was a shining collection of African American excellence and industry.

By the end of the Civil War, Athens had a majority-minority population. This meant that for the first time in their lives, African American Athenians could have a say in the legislature. As a way to encourage voting participation among African American people, Union Leagues were created. The Union League met at the location of what is now Dawg Gone Good BBQ, across from Little Kings. Through their effort of voter registration and advocacy, the Union Leagues were able to elect Athens natives and formerly enslaved people Madison Davis and Alfred Richardson to the state legislature in 1868, along with 29 other African American men from throughout the state. Davis spent some time as a customs surveyor before he was made captain of Relief No.2, which was Clarke County’s first African American fire company. He was also involved with the purchase of the land for the Knox Institute, a school for African American children in the late 19th and early 20th century. Alfred “Alf” Richardson quickly became the target of the Ku Klux Klan for his views and the color of his skin. Richardson introduced a bill that was intended to help regulate wages for new free laborers in the state. To ensure fairness, he wanted the oversight of the Freedmen’s Bureau in addition state oversight. He also advocated for the eight-hour workday, for women’s suffrage, and for some of the provisions that would be adopted by the 1964 Civil Rights Act nearly a century later.

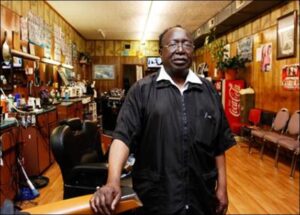

Homer Wilson poses for a portrait at Wilson’s His and Hers Styling Shop on March 6, 2018, in Downtown Athens. (Photo/Christina R. Matacotta)

Wilson’s Styling Shop

Homer Wilson, owner of Wilson’s Styling Shop, says that he got the idea to be a businessman when he visited Hot Corner as a child. The “feeling of it was real city-like,” he said in an interview in 2014 for the Athens Oral History Project. He describes five and ten cent stores, billiard parlors near the Morton Building, markets, and a thriving business culture. Fellow business owner and police officer Archibald Killian said that “you go down there, get your haircut, get you a beer, get a pig-ear sandwich, and just have a good time.”

Mr. Wilson’s Styling Shop was purchased from Mr. Ed Gillum (whom Mr. Wilson explained always made sure that he was referred to with the proper honorific) who purchased from another African American business owner in the same location. Today, Mr. Wilson’s signs still adorn the store fronts of his shops and loyal customers fill up the shop every day. Mr. Wilson is also the head of the Hot Corner Association. Since 1999, the Hot Corner Association has hosted a weekend-long festival to highlight the area’s history.

The Manhattan Café, 337 N. Hull Stree

Hot Corner During & After the Civil Rights Movement

During the Civil Rights movement and protests in the 50s and 60s, Hot Corner was a sort of safe haven for African American protesters. During the protests for the integration of the Varsity, protesters recount going to The Manhattan, a prominent African American-owned restaurant that would give them the time and safety to plan their next move. The Manhattan provided free meals for protesters. Ironically, after integration, minority owned businesses in Athens began to search for locations outside of the downtown district. Mr. Wilson remembers his father’s advice: “Son, you hang in there, because one day, everybody’s going to want to be back downtown.” Mr. Wilson and his brother both advocate for more minority-owned businesses downtown and try to maintain the culture that once flourished here. Though Hot Corner has evolved over the years, it remains a beacon of hope and opportunity in the downtown district.